WHERE YOU COME FROM IS GONE

Collaboration with Cary Norton

Where You Come From is Gone explores the importance of place, the passage of time, and the political dimensions of remembrance through the historical wet-plate collodion photographic process. Created on the eve of Alabama’s bicentennial, Ragland and Norton’s large-scale images seek to make known a history that has largely been eliminated and make visible the erasure that occurred in the American South between Hernando de Soto’s first exploitation of native peoples in the 16th century and Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act 300 years later.

Using a 100-year-old field camera and a custom portable darkroom tailored to Ragland’s 4x4 truck, the two photographers journeyed more than 3,000 miles across 30+ counties in Alabama and Florida to locate, visit, and photograph indigenous sites. Yet the melancholy landscapes hold no obvious vestiges of the Native American cultures that once inhabited the sites; what one would hope to document, hope to preserve, hope to remember, is already gone. Instead, Ragland and Norton deliberately document absence and seek to render the often invisible layers of culture and civilization, creation and erasure, and the man-made and natural character of the landscape. The result is a body of landscape photographs in which the subject matter seems to exist outside of time, despite the fact that the project is explicitly about the passage of time, the slippage of memory, and the burying of history. While the relative emptiness of the landscapes elicits a sense of loss or absence, the beauty of the photographs conveys a continued sacrality of the space and puts viewers in touch with history and memory, helping us not only to imagine what may have been but also how best to honor what is, and what has been lost.

The artists’ deliberate use of the demanding, antiquated wet-plate process strategically highlights the materiality and physicality of both process and photograph, simultaneously uncovering a forgotten history and creating an archival object commemorating the sites photographed. The tintypes are digitally enlarged to 40x50 inch prints to impress upon viewers the magnitude of the landscape and all that transpired there.

Victims of violence, warfare, and cultural displacement, the Eastern Woodland tribes were forced to uninhabit the sites that Ragland and Norton photograph. Conversely, these images seek to encourage viewers to responsibly reinhabit the space rather than continuing on as uninformed, uninvolved residents. At this current moment in American life, the act of remembering is political and can have power, particularly when a polarizing president places a portrait of Andrew Jackson in the Oval Office and whose policies endanger the environment, dispute Native American land rights, and further disenfranchise marginalized citizens. In this way, Where You Come From is Gone works as a type of subtle activism by focusing on personal and collective memory-making. Through reasoned confrontation with our history and resistance toward (willful or accidental) cultural amnesia, these photographs provide a defense against the sort of ignorance that threatens democracy and enables totalitarianism and cautions us to be vigilant in guarding against altering, erasing, or “forgetting” our past.

– Catherine Wilkins, Ph.D., University of South Florida, 2017

.....................................

Solo Exhibitions:

Select Group Exhibitions:

Select Presentations:

Select Publications:

Awards:

.....................................

Where You Come From is Gone explores the importance of place, the passage of time, and the political dimensions of remembrance through the historical wet-plate collodion photographic process. Created on the eve of Alabama’s bicentennial, Ragland and Norton’s large-scale images seek to make known a history that has largely been eliminated and make visible the erasure that occurred in the American South between Hernando de Soto’s first exploitation of native peoples in the 16th century and Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act 300 years later.

Using a 100-year-old field camera and a custom portable darkroom tailored to Ragland’s 4x4 truck, the two photographers journeyed more than 3,000 miles across 30+ counties in Alabama and Florida to locate, visit, and photograph indigenous sites. Yet the melancholy landscapes hold no obvious vestiges of the Native American cultures that once inhabited the sites; what one would hope to document, hope to preserve, hope to remember, is already gone. Instead, Ragland and Norton deliberately document absence and seek to render the often invisible layers of culture and civilization, creation and erasure, and the man-made and natural character of the landscape. The result is a body of landscape photographs in which the subject matter seems to exist outside of time, despite the fact that the project is explicitly about the passage of time, the slippage of memory, and the burying of history. While the relative emptiness of the landscapes elicits a sense of loss or absence, the beauty of the photographs conveys a continued sacrality of the space and puts viewers in touch with history and memory, helping us not only to imagine what may have been but also how best to honor what is, and what has been lost.

The artists’ deliberate use of the demanding, antiquated wet-plate process strategically highlights the materiality and physicality of both process and photograph, simultaneously uncovering a forgotten history and creating an archival object commemorating the sites photographed. The tintypes are digitally enlarged to 40x50 inch prints to impress upon viewers the magnitude of the landscape and all that transpired there.

Victims of violence, warfare, and cultural displacement, the Eastern Woodland tribes were forced to uninhabit the sites that Ragland and Norton photograph. Conversely, these images seek to encourage viewers to responsibly reinhabit the space rather than continuing on as uninformed, uninvolved residents. At this current moment in American life, the act of remembering is political and can have power, particularly when a polarizing president places a portrait of Andrew Jackson in the Oval Office and whose policies endanger the environment, dispute Native American land rights, and further disenfranchise marginalized citizens. In this way, Where You Come From is Gone works as a type of subtle activism by focusing on personal and collective memory-making. Through reasoned confrontation with our history and resistance toward (willful or accidental) cultural amnesia, these photographs provide a defense against the sort of ignorance that threatens democracy and enables totalitarianism and cautions us to be vigilant in guarding against altering, erasing, or “forgetting” our past.

– Catherine Wilkins, Ph.D., University of South Florida, 2017

.....................................

Solo Exhibitions:

- Leepa-Rattner Museum of Art, St. Petersburg College, Tarpon Springs, FL, 2021

- Mason-Scharfenstein Museum of Art, Piedmont College, Demorest, GA, 2020

- UCM Gallery of Art & Design, University of Central Missouri, Warrensburg, MO, 2019

- Staple Goods, New Orleans, LA, Feb-March, 2019

- Georgine Clarke Alabama Artists Gallery, Montgomery, AL, 2018

- North Floor Gallery, Lowe Mill, Huntsville, AL, 2017

Select Group Exhibitions:

- Earth Photo, traveling: Royal Geographical Society, London, UK; Dalby Forest, North Yorkshire, UK; Grizedale Forest, Cumbria, UK; Moors Valley Country Park and Forest, Dorset, UK

- B20: Wiregrass Biennial, Wiregrass Museum of Art, Dothan, AL

- Currents, Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans, LA, curated by Anjuli Lebowitz

- SPESC Juried Educator Exhibition, Firehouse Gallery, Baton Rouge, LA, curated by Russell Lord

- B18: Wiregrass Biennial, Wiregrass Museum of Art, Dothan, AL

- Uncommon Territory: Contemporary Art in Alabama, Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, Montgomery, AL, curated by Jennifer Jankauskas

- Red Clay Survey, Huntsville Museum of Art, Huntsville, AL

- Art Through the Lens, Yeiser Art Center, Paducah, KY

- Sense of Place, Gertrude Herbert Institute of Art, Augusta GA

Select Presentations:

- “Where You Come From is Gone,” Wiregrass Museum of Art, November 2, 2020

- “Where You Come From is Gone: Reinhabiting the Ruins of the Native South,” Below the Mason-Dixon Line: Artists and Historians Considering the South, panelist, College Art Association 2019 Annual Conference, New York, NY, February 15, 2019 (with Catherine Wilkins)

- “Where You Come From Is Gone: Examining the Political Dimensions of Remembrance Through the Wet-Plate Collodion Photographic Process,” Artist Presentation, Society of Photographic Education South Central Regional Conference, Baton Rouge, LA, October 6, 2018

Select Publications:

- Catherine Wilkins. “Jared Ragland: Photography and the Cultivation of Visual Citizenship.” Interdisciplinary Humanities, forthcoming.

- Catherine Wilkins. “Where You Come From is Gone: Reinhabiting the Ruins of the Native South.” Art Inquiries, 2019, Volume 17, Number 4: 440-455.

- D. Eric Bookhardt. “Art review: ‘Where You Come From is Gone’ and ‘The Valley Below.’” Gambit Weekly. Volume 30, Number 14, April 2-8 2019.

- Where You Come From is Gone: booooooom.com.

- Indigenous People’s Day – Wiregrass Museum of Art’s #wmaINSPIRED blog: wiregrassmuseum.org.

Awards:

- 2020 Sacred: The Experience of Beyond, Urbanautica international call, Winner

- 2020 Clarence John Laughlin Award, New Orleans Photo Alliance, Finalist

.....................................

FLORIDA

Commissioned by the Leepa-Rattner Museum of Art and presented in collaboration with representatives of the Seminole Tribe of Florida and the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, 2020.

Chocochatti, Hernando County, Florida, 2020; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

Throughout the 18th century, Indigenous refugees fleeing northern wars and encroachment of white colonists migrated to Spanish Florida. Yamasee, Muscogee (Creek), Choctaw, and Chickasaw from the Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi joined with the descendants of historic Florida tribes and formerly enslaved freedom seekers. Together they formed the yat’siminoli (a derivation of the Spanish “cimarron,” which translates most closely to “runaway” though the tribes designated as “free”). The first colony of Muscogee from Alabama was established in present-day Hernando County in 1767. Initially called “New Yufala” by white explorers, the very first village of the Seminole nation later became known as Tcuko tcati (Chocochatti), meaning “Red House” or “Red Town.” With its fertile farmland and abundance of game, Chocochatti was home to prosperous commercial deer hunters, traders, farmers, and cattlemen for nearly 70 years. But as General Andrew Jackson completed his Creek War campaign in the Alabama Territory, he advanced southward across Florida’s international boundaries and began the first in a series of Seminole Wars. Several skirmishes between the Seminoles and US troops were fought near Chocochatti during the later phases of the Second Seminole War, and in June 1840, US infantry destroyed Chocochatti’s flourishing agricultural fields and burned the village. By 1843, after fighting in open-field, nonconventional guerrilla warfare and committing almost 40 million dollars to the forced removal of the Seminoles, the US withdrew as nearly 4,000 Seminoles were forced to move west onto reservations. However, the Seminoles who wished to remain in Florida were allowed to do so, but were pushed further south into the Everglades.

Jungle Prada Site, Pinellas County, Florida, 2020; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

The Tocobaga inhabited the Tampa Bay area 500-1000 years ago, living in coastal villages characterized by large mounds of earth or shell that kept homes and temples safe from heavy rains and flooding. Measuring over 800 feet long, 300 feet wide, and 23 feet tall, the 900-year-old shell midden at the Jungle Prada site is the best-preserved Tocobaga Indian mound in Tampa Bay. In Spring of 1528 Spanish conquistador Pánfilo de Narváez landed at or near the site, where his 600-man expedition performed the first Catholic Mass in Florida and declared divine right to the land. Scholars estimate that between 1492-1832, more than 1.86 million Spaniards settled in the Americas. Conversely, the Indigenous population plummeted by an estimated 80% in the first century and a half of colonial exploration, primarily due to the spread of Afro-Eurasian disease.

Weedon Island Mangroves, Pinellas County, Florida, 2020; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

Weedon Island was once home to the Weeden Island Culture (alternative spelling) of Florida Gulf Coast dwellers. Developed out of a segment of the Manasota Culture and lasting some 800 years, the Weeden Island Culture is known for its sophisticated ceremonial and utilitarian pottery, mound complexes, and dugout canoes. In 2001, archaeologists unearthed a 1,100-year-old Weeden pine canoe measuring nearly 40 feet in length and featuring a raised bow, indicating that it would have been used on open water.

Weeki Wachee Springs, Hernando County, Florida, 2020; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

Paleo-Indians first arrived in the Weeki Wachee Springs area some 13,000 years ago, settling in an area much cooler and drier than today’s climate, with the Gulf of Mexico 200 feet lower than current levels. Over the following 10,000 years, the Deptford Culture people developed hunting/gathering settlements along the Gulf, eventually giving way to the Weeden Island Culture (200-1200 AD) who were known for their use of ceramics and ceremonial mound complexes. Evidence of the Safety Harbor Culture people dating from 1,000 to 450 years ago have been excavated from a burial mound at Weeki Wachee Springs, which also contained early Spanish Contact Period artifacts. Wekiwa Chee – a Seminole name meaning “little spring” or “winding river” – is a first-magnitude spring and daily discharges more than 117 million gallons of fresh water from subterranean caverns so deep that the bottom has never been found.

Espiritu Santo Springs, Pinellas County, Florida, 2020; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

On May 18, 1539, Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto reached the shores of what is now Tampa Bay, landing near a series of mineral springs used by indigenous peoples for nearly 10,000 years. Believing he had found the legendary Fountain of Youth somehow missed by Ponce de Leon, de Soto established a camp and named the crystal waters Espiritu Santo Springs (Springs of the Holy Spirit). Each of the five springs located on this site are said to cure certain ailments, a claim drawing thousands of visitors yearly to the "Health Giving City" of Safety Harbor. Some 400 years after de Soto's arrival, the Safety Harbor Sanitorium opened its doors, offering porcelain bath tubs and a large swimming pool for "taking the waters." Yet it was de Soto – and other European expeditions that had followed Columbus to the New World – that took Afro-Eurasian diseases like smallpox, measles, and influenza to the continent, killing more than 50 million indigenous people between 1492 and 1600.

Egmont Key, Florida, 2020; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

The United States government began forcibly removing Native Americans from Florida in 1817. As Eastern Woodland peoples throughout the southeast were forced to leave their homelands for reservations in Oklahoma, the Seminoles – an already displaced people – were removed by steamship in an over-water branch of the Trail of Tears. One such vessel, the Grey Cloud, made more than two dozen voyages during the Second and Third Seminole Wars from a stockade on Egmont Key, a small secluded island located in the mouth of Tampa Bay. At one time, the stockade held as many as 300 Seminoles, including Holata Micco (Billy Bowlegs), one of the last Seminole chiefs to resist forced removal; Emateloye (Polly Parker), who escaped the Grey Cloud while docked near Tallahassee and walked 400 miles southward to rejoin her people at Lake Okeechobee, where she lived until her death in 1921; and Seminole leader Thlocklo Tustenuggee (Tiger Tail), who committed suicide by swallowing crushed glass rather than remain in captivity. It is also said ten Seminole warriors detained at Egmont marched silently into the Gulf instead of suffering relocation. Many other Seminoles died while interned on the island, but names and burial locations were not accurately recorded by the US government. Over the last century, Egmont Key has lost more than half its land mass – and with it its important history – as the seas surrounding the island have risen at least 8 inches. State officials predict another 9- to 24-inch rise by 2060, while wakes churned by fuel tankers, container ships, and cruise liners in Tampa Bay increasingly erode the island’s dunes.

Weedon Island, Pinellas County, Florida, 2020; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

Spanning approximately 3,700 acres, Weedon Island is located on the shores of Old Tampa Bay and is Florida’s largest estuary. The Weedon coastal system is comprised of a variety of aquatic and upland ecosystems, and has been occupied by human populations since the Middle Archaic period (5000-3000 BCE). The island was once home to the Yat Kitischee people of the late Weeden Island Culture (alternative spelling), who along with the nearby Safety Harbor Culture formed the major centers of political, ceremonial and social significance on the Pinellas Peninsula around 200-1000 CE. The Weeden Island Culture is known for its sophisticated ceremonial and utilitarian pottery, mound complexes, and dugout canoes. Today, much of the estuary is managed under preservation efforts, but legacy effects of mosquito ditching in the 1950s have made salt marshes more vulnerable to flooding impacts from climate change.

Tierra Verde, Pinellas County, Florida, 2020; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

Near this site, south of present-day St. Petersburg, a Tocobaga charnel house and burial mound were once situated on a series of 15 islands. Scholars believe the dead would be laid in the charnel house and a shaman/priest – with help from scavenging birds – would remove the flesh from the skeleton in preparation for burial. Once stripped or picked cleaned, the bones and the eternal spirit they held were placed in the mound. The Tocobaga disappeared from the historical record by the early 1700s, as disease brought by European explorers decimated the Safety Harbor culture, leaving the Tampa Bay area virtually uninhabited for more than a century. The landscape of Tierra Verde was completely transformed in the late 1950s when the burial grounds were razed and used as fill dirt for a residential development and golf course.

.....................................

ALABAMA

2017-2020

Bessemer Mounds, Jefferson County, Alabama, 2017; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

The Bessemer Mounds area was first occupied as early as 5,000 years ago, with a Woodland and Mississippian settlement site located along the banks of Valley Creek near present-day Bessemer. Three mounds were constructed around 1100 CE, predating those found 75 miles southeast at the historically-preserved Moundville Archeological Park. The mounds at Bessemer were leveled in the early 1900s following archaeological excavation; a water sewage plant, Amazon fulfillment center, and VisionLand, a defunct theme park, are now located near the site.

Bessemer Mounds, Jefferson County, Alabama, 2017; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

Garrett Cemetery, Cherokee County, Alabama, 2017; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

Outside the gates of the Garrett Cemetery is the final resting place of Pathkiller, the last hereditary chief of the Cherokee. During the American Revolution Pathkiller allied himself with the British and fought against American troops, but by 1813 he had sided with Andrew Jackson’s militia in the Creek Wars. Just three years after Pathkiller’s death, Jackson betrayed his former alliance with the Cherokee, reneged established treaties, and forced the Cherokee from their ancestral homelands.

Coosa River, Cherokee County, Alabama, 2017; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

Cahaba River, Dallas County, Alabama, 2017; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

Old Cahawba, Dallas County, Alabama, 2017; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

For millennia people have been drawn to the land situated at the confluence of the Cahaba and Alabama rivers. The area now known as Old Cahawba was first occupied by large populations of Paleoindians 4,000 years ago. During the Mississippian period (1000–1500 CE), mound builders established a walled city with palisades that was visited by Spanish conquistadors in the 16th century. In the years that followed, Afro-Eurasian diseases the explorers brought with them killed thousands of Indigenous people, and the remaining native peoples were wiped out or forced to move by an even greater influx of Europeans. By the early 19th century, the dirt from the ancient mounds at Cahawba was used to build railroad beds, and the town briefly served as the state capital of Alabama. Cahawba became a ghost town shortly after the Civil War, largely due to recurring floods. By the late 1800s, the town site was purchased for $500 and its buildings demolished.

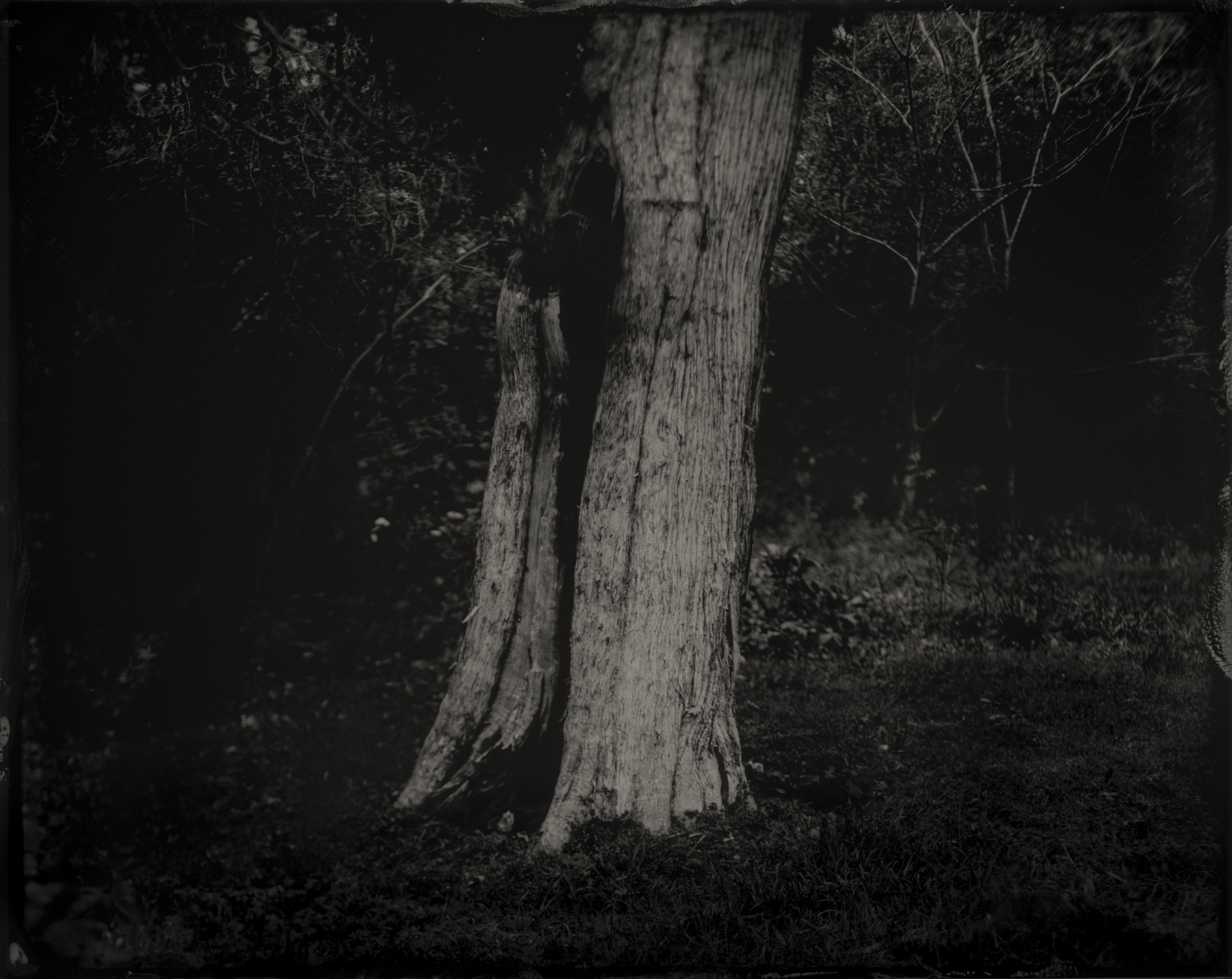

Cedar tree at Manitou Cave (Willstown), DeKalb County, Alabama, 2017; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

Many Indigenous tribes attribute special spiritual significance to cedar trees. In particular the Cherokee, who inhabited Willstown and the surrounding area, believe that cedar trees hold the spirits of deceased ancestors and therefore possess the power of protection. Inside Manitou Cave traces of human activity date back 10,000 years. The cave also includes inscriptions from the Cherokee syllabary, invented by Sequoyah while he lived in Willstown in the early 1800s. After the Cherokee removal on the Trail of Tears the cave was used as a Confederate encampment and saltpeter mine; in the 1920s it was converted into a tourist destination where flappers danced the Charleston in a “ballroom” that featured electric lights; and during the Cold War it was outfitted as a fallout shelter. After decades of neglect the cave is the focus of grassroots historical and environmental protection and in 2016 was listed by the Alabama Trust for Historic Preservation as one of the state’s “Places in Peril.”

Unnamed island on the Coosa River, Cherokee County, Alabama, 2017; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

Near this site stood the great Native American city of Chiaha, where in 1540 Hernando de Soto stood on the banks of the river and marveled at “the beauty and richness of the land” and was warmly welcomed by a soon to be occupied and enslaved people.

Cherokee Rock Village, Cherokee County, Alabama, 2017; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

Cherokee Rock Village was home to Indigenous peoples almost continuously from 8000 BCE until the 1830s, when the resident Cherokee and Muscogee (Creek) peoples were forcibly removed by the Indian Removal Act. Located along an ancient Native American trail of religious and ceremonial importance, the site later became a starting point for the Trail of Tears.

Near DeSoto Falls, DeKalb County, Alabama, 2017; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

In June 1540, a small scouting group from de Soto’s army of conquistadors made their way up Lookout Mountain to what is today known as DeSoto Falls, where they searched the area for gold and precious stones.

Ten Islands, St. Claire County, Alabama, 2017; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

In July of 1540 Hernando de Soto and his men forded the Coosa River near this point at Ten Islands. In tow were enslaved Indigenous people, forced to accompany the Spaniards and carry their supplies. Some 250 years after de Soto’s visit, the site became home to General Andrew Jackson’s Fort Strother, from which he began his campaign against Red Stick Muscogee Creeks during the Creek Wars in 1812. Over the last two centuries, the Coosa River has been harnessed to capitalize on its economic potential. In the 1880s, a series of river locks were constructed at Ten Islands to expand commercial shipping; today the river holds seven Alabama Power Company dams, including the nearby H. Neely Henry Dam.

Moundville, Hale County, Alabama, 2017; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

Moundville was the political and ceremonial center of a Mississippian chiefdom on the Black Warrior River in west Alabama between the 11th and 15th centuries. More than 10,000 people lived at and around the 300 acre site, which featured more than 30 earth mounds used for civic and religious purposes, with the layout of the mounds likely placed in cosmological symbolic order and regarded by Mississippian peoples as the doorway to the afterlife. While the site stood as the second largest city in North America for generations, it had been abandoned by the time Europeans began exploring the area in the 16th century.

Ohatchee, Calhoun County, Alabama, 2017; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

Near this spot a marker stands memorializing the place where General Andrew Jackson found and adopted an orphaned Muscogee (Creek) baby in November 1813. The story recounts how the baby was found in his dead mother’s arms and Jackson had such compassion that he took the child and raised him as his own. What the marker does not report is that it was also near this location that Jackson’s Tennessee militia began their genocide of the Red Stick Muscogee Creek Confederacy. The day before Jackson found the child, his forces trapped Muscogee men, women and children inside their log homes and burned them alive. In his memoirs, Tennessee Volunteer Davy Crocket wrote that the few Creek who escaped were “shot down like dogs.” The ultimate defeat of the Red Sticks during the Creek Wars led to the loss of 23 million acres of ancestral land. The final treaty was dictated by Jackson, who after the conflict would be promoted to Major General before being elected the seventh president of the United States in 1829. As president, Jackson’s top legislative priority was Native relocation, and he signed the Indian Removal Act into law in 1830, sanctioning a unitary act of systemic genocide upon southern Native American tribes.

Tuckabatchee, Elmore County, Alabama, 2019; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

The Muscogee (Creek) mothertown of Tukabatchee is believed to be the first site of the ancient ‘busk’ fire which began the Green Corn Ceremony, an annual ritual practiced among various Native American peoples in which the community would sacrifice the first of the green corn to ensure the rest of the crop would be successful. In 1811, the Shawnee chief, Tecumseh, and Tenskwatawa (better known as the Prophet) addressed Creek leaders in the Tukabatchee town square to convince the Muscogee to join their Pan-tribal campaign against encroaching European settlers. Tecumseh was so disappointed in the Creek response at the end of his speech that he said the Prophet would “...stamp his foot and all of Tuckabatchee’s cabins would fall.” The town was leveled by the New Madrid earthquake a month later.

Econochaca (Holy Ground), Lowndes County, Alabama, 2019; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

In 1813 Red Stick Creeks fought US Army Rangers and militia men at Econochaca (Holy Ground). Muscogee prophets performed ceremonies at the site to create a spiritual barrier of protection, but the Red Sticks lost the battle. Their leader, William Weatherford – known as Red Eagle – barely escaped capture, jumping from a bluff into the Alabama River while on horseback. Weatherford would later go on to lead the Red Sticks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend against Major General Andrew Jackson.

Turkeytown, Cherokee County, Alabama, 2017; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

Established some time prior to 1770, Turkeytown was one of the most important Cherokee cities in the region. Following his victory over the Muscogee Creek Red Sticks, General Andrew Jackson visited his Cherokee allies at Turkeytown in 1816 for a Council of the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), and Chickasaw to negotiate boundaries and ratify a peace treaty as Alabama opened to white settlers. At the council the Cherokee ceded a large portion of their ancestral lands in north-central Alabama to the US government and agreed to the building of roads throughout their domain, including construction of the Alabama Road over the ancient hunting and trading paths that once ran east to Rome, Georgia. By 1830 then President Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act into law, overwriting previously established treaties and forcing the Eastern Woodland tribes – including the Cherokee – westward on the Trail of Tears.

Omussee Creek Mound, Henry County, Alabama, 2019; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

The Omussee Creek Mound was built by the Chacato people, ancestors of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, who held a tenuous relationship with Spanish missionaries. Occupied from approximately 1300 to 1550 A.D., the mound is the southernmot platform mound along the Chattahoochee River and was part one of the densest concentrations of mound centers in North America. Omussee served as a key population and cultural center during the Mississippian era, but by around 1550 the native population in the area was in decline. Many believe this may have been part of a broader, regional depopulation due in large part to the spread of diseases brought by European explorers. Today the mound is difficult to distinguish from the short knolls and hillocks along the banks of the Chattahoochee, and it is covered in trees and dense foliage – much of which had been felled and further tangled during the devastating Category 5 storm, Hurricane Michael, in 2018.

Choctawhatchee River, Geneva County, Alabama, 2019; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

Archaeological evidence suggests that present-day Geneva County was a major center of advanced Native American occupation. Near this point in the Choctawhatchee River, the Muscogee (Creek) built seafaring trade canoes and would traverse from the Wiregrass region of south Alabama into the Gulf of Mexico.

Hodby’s Bridge, Pike County, Alabama, 2019; archival pigment print from wet-plate collodion tintype; 40x50 inches

As treaties guaranteeing Indigenous land rights went unenforced through the 1800’s and settlers moved into Muscogee (Creek) territory, many fought back against the violent appropriation of their land. Others chose to move south instead of west and traveled to Florida, following a route along the Pea River. In March of 1836, Alabama Militia forces led by U.S. General William Wellborn tracked 400 Muscogee to their camp near Hodby’s Bridge and attacked. It is said that much of the fighting occurred in waist-high water and deep mud, with women and children taking up arms alongside Muscogee warriors who used bullets made from melted pewter plates. At least 50 Muscogee men were killed, with an unknown number captured. According to some reports, some of the captured were enslaved by local planters.

.....................................

INSTALLATION

Where You Come From is Gone, University of Central Missouri, Warrensburg, MO, 2019

Where You Come From is Gone, North Floor Gallery, Lowe Mill, Huntsville, AL, 2017

.....................................