WHAT HAS BEEN WILL BE AGAIN

What Has Been Will Be Again was initiated by a 2020 Do Good Fund artist residency and made with support from a 2020 Magnum Foundation U.S. Dispatches grant, 2021 Aftermath Project 1492/1619 American Aftermaths Grant, 2022 Columbus State University artist residency, 2025 Brooklyn Darkroom artist residency, and 2025 Center for Photographic Art Mid-Career Artist Grant. Additional support was provided by the Alabama State Council on the Arts, Coleman Center for the Arts, Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, Wiregrass Museum of Art, and Utah State University.

American exceptionalism, that sense that we are somehow special and ordained as such, is a myth sedimented on Southern prosperity… But even if you are a lover of the national romance, integrity requires that the stories be at least halfway honest. It is not enough to set aside a little time or attention here or there to grieve our national sins, then, soft as butter, turn back to proclamations of greatness. Because history is an instruction. And what you neglect to attend to from the past, you will surely ignore in the present.

– Imani Perry, South to America

Alabama has known a deep and complex history. From Indigenous genocide to slavery and secession, and from the fight for civil rights to the championing of MAGA ideology, the national history written on, in, and by the people and landscapes of Alabama reveal problematic patterns at the nexus of larger American identity.

Working deep in territory considered a repository of national repressions, What Has Been Will Be Again has led Jared Ragland across more than 25,000 miles and into each of Alabama’s 67 counties to trace routes connected to brutal colonial legacies—including the path of Hernando de Soto’s 1540 expedition, the Trail of Tears, and the Old Federal Road.

Social isolation is both a phrase and experience that has defined the recent past, and What Has Been Will Be Again expressly evokes the alienation that has characterized the moment. Yet the work considers sites for which isolation is nothing new—places where extracted labor and environmental exploitation have exacted heavy tolls for generations. Such isolation is less accidental or temporal, and more a product of decades of willful neglect by a mainstream America only now starting to visualize what—and who—has been pushed out of the collective frame of vision.

By combining a Southern Gothic visual sensibility with narrative captions, the photographs strategically focus on the importance of place, the passage of time, and the visual-political dimensions of remembrance to confront White supremacist myths of American exceptionalism and challenge the silence of historical narratives that have so long failed to speak the names, dates, and places where such violence and marginalization has occurred.

Download project PDF here: Ragland-WHBWBA.pdf

See the project reading list here.

Why “White” is capitalized in reference to race in WHBWBA: Capitalizing Black and White: Grammatical Justice and Equity

.....................................

American exceptionalism, that sense that we are somehow special and ordained as such, is a myth sedimented on Southern prosperity… But even if you are a lover of the national romance, integrity requires that the stories be at least halfway honest. It is not enough to set aside a little time or attention here or there to grieve our national sins, then, soft as butter, turn back to proclamations of greatness. Because history is an instruction. And what you neglect to attend to from the past, you will surely ignore in the present.

– Imani Perry, South to America

Alabama has known a deep and complex history. From Indigenous genocide to slavery and secession, and from the fight for civil rights to the championing of MAGA ideology, the national history written on, in, and by the people and landscapes of Alabama reveal problematic patterns at the nexus of larger American identity.

Working deep in territory considered a repository of national repressions, What Has Been Will Be Again has led Jared Ragland across more than 25,000 miles and into each of Alabama’s 67 counties to trace routes connected to brutal colonial legacies—including the path of Hernando de Soto’s 1540 expedition, the Trail of Tears, and the Old Federal Road.

Social isolation is both a phrase and experience that has defined the recent past, and What Has Been Will Be Again expressly evokes the alienation that has characterized the moment. Yet the work considers sites for which isolation is nothing new—places where extracted labor and environmental exploitation have exacted heavy tolls for generations. Such isolation is less accidental or temporal, and more a product of decades of willful neglect by a mainstream America only now starting to visualize what—and who—has been pushed out of the collective frame of vision.

By combining a Southern Gothic visual sensibility with narrative captions, the photographs strategically focus on the importance of place, the passage of time, and the visual-political dimensions of remembrance to confront White supremacist myths of American exceptionalism and challenge the silence of historical narratives that have so long failed to speak the names, dates, and places where such violence and marginalization has occurred.

Download project PDF here: Ragland-WHBWBA.pdf

See the project reading list here.

Why “White” is capitalized in reference to race in WHBWBA: Capitalizing Black and White: Grammatical Justice and Equity

.....................................

Select Publications:

Select Solo Exhibitions:

Select Group Exhibitions:

Select Awards:

.....................................

Select Works:

Each image is produced as an archival pigment print, 21x24.5 inches

![Spring Hill, Barbour County — Michael Farmer. Michael Farmer’s family has lived in Spring Hill for generations, where the predominantly Black community has faced a history of racial violence and voter disenfranchisement. On November 3, 1874 a White mob attacked the Spring Hill polling station, destroyed the ballot box, burned the ballots, and murdered the election supervisor’s son. According to the Equal Justice Initiative, many of the perpetrators of the massacre were known, but no one was ever convicted. Instead, a Black man named Hilliard Miles was imprisoned after identifying members of the mob. Decades later, BB Comer, whom Mr. Miles had named as one of the perpetrators of the massacre, was elected governor of Alabama. While 1,200 local Black residents voted in the 1874 election, only 10 cast ballots in 1876. Almost 150 years later, little has changed. In 2016, Barbour County had the highest voter purge rate in the United States.]()

![Childersburg, Talladega County — Sunshine turns soil in the Commons Community Workshop garden. As a response to national division and the COVID-19 outbreak, Sunshine and her husband Rusty bought a home in downtown Childersburg and created The Commons Community Workshop. Through their Fearless Communities Initiative they maintain a community garden in a donated downtown lot, host trade days, and foster relationships with their neighbors as a means of “celebrating solidarity and strength.” The couple invited me to find them on Facebook where Sunshine posts Initiative announcements, vocalizes her opposition to vaccines, and shares her beliefs about global child sex trafficking networks, the threat of Marxism, and the coming of the end times.]()

![Jacksonville, Calhoun County]()

![Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County — Glitter scattered on ruins of the former state capitol building. Yoholo-Micco, chieftain of the Upper Creek town of Eufaula, is said to have addressed the Alabama Legislature in 1836 at the state capital in Tuscaloosa before departing the ancestral Muscogee homelands on the Trail of Tears. Yoholo-Micco’s actual words are unknown, but White, colonial writers of history have portrayed the Creek leader as one who accepted Indigenous removal with an air of romantic resignation, going so far as to contrive his final words in a way to whitewash the genocide that had taken place over 300+ years’ time. Yoholo-Micco’s apocryphal address—which has been reproduced in Alabama history books and grade school curriculum for decades—reads, in part: “I come here, brothers, to see the great house of Alabama and the men who make laws and say farewell in brotherly kindness before I go to the far west, where my people are now going. In time gone by I have thought that the White men wanted to bring burden and ache of heart among my people in driving them from their homes and yoking them with laws they do not understand. But I have now become satisfied that they are not unfriendly toward us, but that they wish us well.”]()

![Ensley, Jefferson County — Tuxedo Junction]()

![Marion, Perry County — Birthplace of Coretta Scott King. Coretta Scott and Martin Luther King, Jr. were married on June 18, 1863 at her family home in Marion. That evening, the couple was rejected by a Whites-only hotel in nearby Marion and were forced to spend their wedding night in a home that served as a Black-owned funeral parlor.]()

![Talladega County — Mt. Ida Plantation. Destroyed by fire in 1956, the 1840 Greek Revival-style antebellum mansion was built for Walker Reynolds, who owned some 13,000 acres of land and several hundred enslaved persons. The plantation was located near the site of Abihka, once one of four mother towns of the Muscogee Creek confederacy.]()

![Hayneville, Lowndes County — Site of Varner’s Cash Store, where Civil Rights activist Jonathan Myrick Daniels was shot to death by Tom Coleman. Jonathan Myrick Daniels, a White Episcopal seminarian from Keene, NH, had come to Alabama following Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s call for clergy to join the march from Selma to Montgomery. Daniels remained in Alabama after the march, assisting with voter registration efforts, working at a health clinic, and helping integrate an Episcopal congregation. In August 1965 Daniels and fellow activists attempted to purchase drinks at a Hayneville store but were held at gunpoint by volunteer special deputy sheriff Tom Coleman, who demanded they leave the property. Coleman shot at 17-year old African American activist Ruby Sales, but Daniels pushed Sales to the ground and took the impact of the blast, dying instantly. Coleman was charged with manslaughter, and despite death threats made to her and her family, Sales testified at trial. However, the all-White jury acquitted Coleman of all charges after deliberating for less than two hours. A year after the killing, Coleman said he had no regrets and would “shoot them both tomorrow.”]()

![Ft. Payne (formerly Willistown), DeKalb County — Manitou Cave. In 1837 federal troops seized Cherokee property around Willstown and established Fort Payne, a stockade and emigration depot for Indian Removal. The majority of Cherokee in Alabama who were forced to leave their homes by the Indian Removal Act of 1830 were interned at Fort Payne. By October of 1838, less than a year after the fort’s establishment, a detachment of 1,100 Cherokee led by Cherokee conductor John Benge departed for Indian Territory and the fort closed soon after. Inside Manitou, traces of human activity date back 10,000 years. The cave includes sacred inscriptions written in Cherokee syllabary, which was invented by Sequoyah while he lived in Willstown in the early 1800s. After Indian removal the cave was used as a Confederate encampment and saltpeter mine; by the end of the 19th century industrialists mined the cave for iron and developed the area as a tourist attraction; in the 1920s it was converted into a tourist destination where flappers danced the Charleston in a “ballroom” that featured a wooden dance floor and electric lights; and during the Cold War it was outfitted as a fallout shelter. Through the mid-20th century the site was a roadside attraction but closed after the interstate drew traffic away from Ft. Payne. After decades of neglect the cave is now the focus of grassroots historical and environmental protection.]()

![Old Cahaba, Dallas County — Perine Well. The area now known as Old Cahawba was first occupied by large populations of Paleoindians; then from 1000-1500 CE the Mississippian period brought agriculture and mound builders. Spanish conquistadors were welcomed to a walled city with palisades, yet the Afro-Eurasian diseases the explorers brought with them killed thousands of Indigenous people in the 16th and 17th centuries. The remaining native peoples were killed or forced to move by an even greater influx of Europeans. By the early 19th century, the dirt from the ancient mounds at Cahawba was used to build railroad beds, and the town briefly served as the state capital of Alabama. At the time it was dug in the 1850s, the Perine Well, at 700-900 feet deep, was the second-largest known well in the world, feeding cool water through a system of pipes to “air condition” a 26-room brick mansion. Cahawba became a ghost town shortly after the Civil War, largely due to recurring floods. By the late 1800s, the town site was purchased for $500 and its buildings demolished.]()

![Macon County — Near the site of Fort Bainbridge. Located near several important Muscogee (Creek) towns along the Old Federal Road, Fort Bainbridge was constructed in 1814 to guard the U.S. Army’s supply route into Creek territory. After the Indian Removal Act of 1830, local White landowners established a plantation system using extensive forced labor of enslaved people. Between 1932 and 1972, investigators from United States Public Health Service and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention enrolled a total of 600 African-American men from Macon County in “The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male.” Participants were not informed of the nature of the experiment and left untreated for 40 years. As a result, 28 patients died directly from syphilis, 100 died from complications related to syphilis, 40 of the patients’ wives were infected with syphilis, and 19 children were born with congenital syphilis.]()

![Carbon Hill, Walker County. Carbon Hill has endured a troubled history of racism and violence. Originally established as a mining and railroad community by the Galloway Coal Company, Carbon Hill’s founders incorporated the town on Valentine’s Day, 1891 and nicknamed it “The Village of Love and Luck.” However, just two weeks prior a group of 200 White coal miners on strike from the Carbon Hill Coal and Coke Co. devolved into a violent mob upon hearing rumors their strike would lead to layoffs. Afraid their jobs would be given to Black workers, the mob terrorized the town. Between 2019-2020 Carbon Hill mayor Mark Chambers published several inflammatory statements on Facebook, including a call to “kill out” the LGBTQIA community, claiming immigrants were “ungrateful,” and aiming racist remarks at the Black Lives Matter movement. Carbon Hill’s population is 89% White and 25% live below the poverty line; more than 83% of local residents voted for Donald Trump in the 2020 election.]()

![Castleberry, Conecuh County — Antonio]()

![Henry County — Clear cut pine forest]()

![Repton, Conecuh County — Dinosaur Adventure Land. DAL is a Christian campground, science center, and adventure park dedicated to anti-evolution teaching. Its founder and leader, Christian fundamentalist Kent E. Hovind, takes a literalist interpretation of the Genesis creation narrative and promotes discredited Young Earth Creationist theories. Before building DAL in Alabama, Hovind operated a similar theme park in Pensacola and served a ten-year sentence in federal prison for failure to pay taxes, obstructing federal agents, and structuring cash transactions.]()

![Holy Trinity, Russell County — Micah (Apalachicola Fort Site). Located across the Chattahoochee River from present-day US Airborne School at Fort Benning, Georgia, a wattle and daub blockhouse fort was established in 1690 by Spain in an attempt to maintain influence among the Lower Creek people. The effect of the construction of the Apalachicola Fort site was that the local Creeks, instead of staying with the Spanish, migrated to English-controlled areas. This move undermined the purpose of the fort, which was already encumbered by a long supply line. It was consequently abandoned after just one year of use, and largely demolished by the Spanish prior to their departure.]()

![Clio, Barbour County — Birthplace of George Wallace]()

![Brookside, Jefferson County — Tobias]()

![Spring Hill, Barbour County]()

![Russell County — Controlled burn]()

![Irondale, Jefferson County — Zeke]()

![Lee County]()

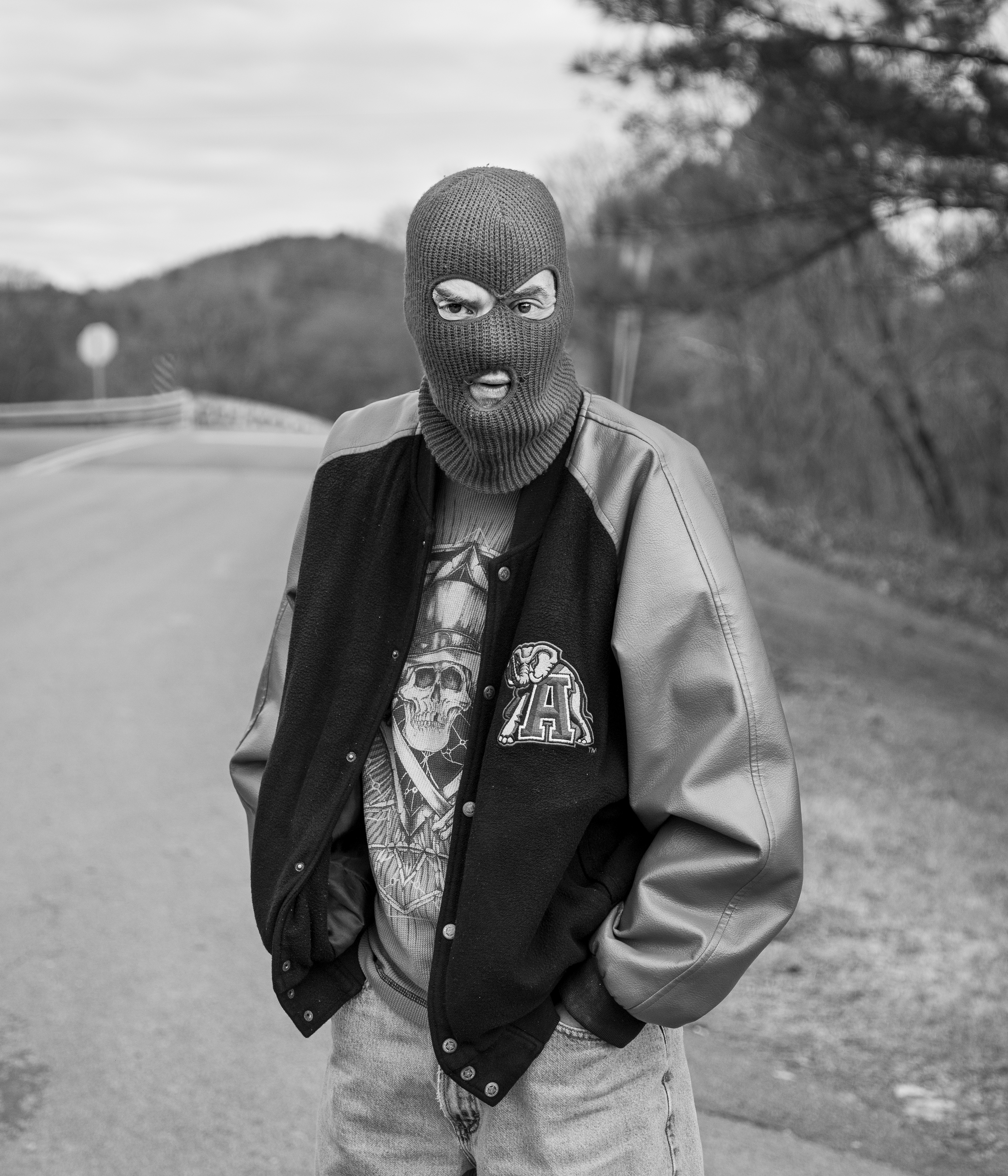

![Walker County — Johnny Slingblade]()

![Thomaston, Marengo County — Calaboose that held Rufus Lesseur. On August 16, 1904, a mob of unmasked White men lynched Rufus Lesseur, a 24-year-old Black man, and left his body riddled with bullets. Less than two days earlier, a White woman in Thomaston claimed that a Black man had entered her home and frightened her. After someone claimed that a hat found near the woman’s home belonged to Lesseur, the mob formed, kidnapped Lesseur, and locked him in a tiny calaboose, or makeshift jail, for more than a day. At 3:00am on August 16, without an investigation, trial, conviction of any offense, or a sentencing proceeding, a mob of White men broke into the locked shack, seized Mr. Lesseur, dragged him outside, and lynched him, filling his body with bullets. Although he was lynched by a mob of unmasked White men in a town with only 300 residents, state officials claimed that no one could be identified, arrested, or prosecuted for Lesseur’s murder. Lesseur is one of at least four Black victims of racial terror violence lynched in Marengo County between 1877 and 1950.]()

![Macon County]()

![Birmingham, Jefferson County — Jeremiah. According to a 2020 investigation by Northeastern University, 123 Black people were killed by White police officers in Jefferson County between 1932–1968. In only two cases were officers charged for the killings. For 26 of the 36 years chronicled, the commissioner of public safety in Birmingham was Eugene “Bull” Connor, who infamously turned fire hoses and attack dogs on Civil Rights protesters in Birmingham in 1963.]()

![Evergreen, Conecuh County]()

![Tallassee, Tallapoosa County. Talisi (“Old Town” in the Creek language) was a town of the Coosa Province of the Mississippian culture; it was visited in 1540 by Hernando de Soto. By the 17th and 18th centuries Muscogee (Creek) people occupied the site, as well as the nearby Creek mother town of Tuckabatchee. The area is believed to be the first site of the ancient ‘busk’ fire which began the Green Corn Ceremony to celebrate the annual corn harvest. Talisi was also the birthplace of Osceola, who, after migrating to Florida and joining the Seminole, led in the resistance of Indian removal and White settlement. The Creek who were forced from Talisi settled in what was later known as Tulsa, Oklahoma. Following White settlement the town developed a textile industry that would later supply uniforms and tents for the Confederacy. In June of 1864, Tallasee Mills was converted into an armory for producing carbines. At the time of their closure in 2005, the Tallassee Mills were the oldest continuously operating textile mills in the United States; the mills were destroyed by fire in 2016. Today the downtown and area surrounding now-demolished mills is largely dispossessed.]()

![Union Springs, Bullock County — Along the Three Notch Road. Built by U.S. Army engineers over the summer of 1824, the Three Notch Road was initially constructed to facilitate military communication between Pensacola, Florida and Ft. Mitchell, Alabama. Following Indian removal it became the major thoroughfare for those coming from Georgia into present-day Bullock County when eastern Alabama was opened to American settlement. Designated “Road No. 6” in official reports, the 233-mile path through a virtual wilderness was known and named locally for the distinctive horizontal notches blazed into trees by advancing surveyors as they marked the route for the builders who followed.]()

![Tuskegee, Macon County — Confederate monument. In recent years Macon County citizens, led by former Tuskegee mayor and city councilman Johnny Ford, have made several attempts to remove or cover the Confederate monument in the town square. Erected by the Daughters of the Confederacy in 1906 on a plot gifted by a then White-controlled county government, the statue became the centerpiece of the Whites-only park–a racist, White supremacist symbol placed in the heart of one of the most historically and culturally significant African American communities in the nation. In July 2021 Ford attempted to topple the monument with a concrete saw, cutting through a leg before being stopped by the local sheriff. “We cannot, in Tuskegee, Alabama, the birthplace of Rosa Parks, the home of the Tuskegee Airmen, the home of Tuskegee University, this historic city, have a Confederate statue in a park built for White people,” Ford said in a report by the AP. Yet recent legal efforts by city officials to remove the statue have stalled, particularly in light of state legislation written to protect Confederate monuments. In February 2022 the Alabama state legislature advanced a bill that would increase the fine for violating the Alabama Memorial Preservation Act of 2017 from a $25,000 one-time fine to $5,000 per day.]()

![Choctaw County]()

![Thomaston, Marengo County — Thomaston Colored Institute. Completed in 1910 by the West Alabama Primitive Baptist Association, the Thomaston Academy was the only significant educational opportunity for the area’s Black population for decades due to segregationist Jim Crow-era policies, including pupil placement acts. Alabama’s School Placement Law, which claimed to allow school boards to designate placement of students based on ability, availability of transportation, and academic background, was designed to defy the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision and maintain school segregation, giving Alabama school boards power to assign individual students to particular schools at their own discretion with little transparency or oversight. In response to the law’s passage, Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth sued on behalf of four African American students in Birmingham who had been denied admission to White schools that were closer to their homes. On November, 24, 1958, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected the challenge. In its unanimous decision, the Supreme Court wrote, “The School Placement Law furnishes the legal machinery for an orderly administration of the public schools in a constitutional manner by the admission of qualified pupils upon a basis of individual merit without regard to their race or color. We must presume that it will be so administered.” Between 1954-58, a total of 376,000 African American children were enrolled in integrated schools across the South. This growth slowed significantly, or was altogether halted, as states passed obstructive legislation. Across the Deep South states, including Alabama, schools remained completely segregated until 1960, barring 1.4 million Black schoolchildren equal opportunity for education. The Thomaston Colored Institute, now abandoned, was included on the Alabama Historical Commission’s Places in Peril in 2000, the same year it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.]()

![Evergreen, Conecuh County — Antoine. Soon after the COVID-19 pandemic began Antoine was released from a court-ordered drug rehab program in Philadelphia. Rather than stay in Pennsylvania, he chose to return to his childhood home in Evergreen, make a new start, and help take care of his ailing mother.]()

![Monroe County]()

![Stewart, Hale County — Christenberry home place.]()

![Monroe County — Near the site of Claiborne. Located along the Alabama River in present-day Monroe County, Claiborne was a once flourishing center of political and economic life in territorial Alabama. Serving as a base of operations during the Creek War in the early 19th century, Claiborne was also home to Alabama’s first Eli Whitney-designed cotton gin. Today, the Georgia-Pacific Alabama River Cellulose paper mill is located just upriver of the old town site. The mill produces specialty fluff and market pulp for consumer products that are found in more than 65% of U.S. households. While in process of switching to sustainable and renewable energy sources and investing in conservation projects, Georgia-Pacific self-reported that the Alabama River Cellulose paper mill released more than 120,000 pounds of reproductive toxins into the Alabama River in 2015.]()

![Phenix City, Russell County — Michael. Located on the Chattahoochee River near the former Creek centers of Coweta and Yuchi Town, Phenix City has known a fraught and violent history. In the mid-20th century, Phenix City was home to the Dixie Mafia, and as murders, prostitution, and gambling ran rampant the town became known as “the wickedest city in the United States.”]()

![Sayre, Jefferson County]()

![Walker County]()

![Sumter County — Near the site of Fort Tombecbe, an 18th cen. stockade built on Choctaw lands. Originally constructed by French colonialists in 1736 on the border of French Louisiana, Fort Tombecbe was positioned to hold back British intrusion into the area and served as a major French outpost and trade depot among the Choctaw. Control passed to the British in 1763, who renamed it Fort York but abandoned the site. In 1793 Spain acquired the site from the Choctaw in the treaty of Boufouka, which ceded approximately 10,000 acres of Choctaw land to the Spanish.]()

![Cottonton, Russell County]()

![Pine Torch, Lawrence County — Bankhead National Forest settler cemetery]() .....................................

.....................................

Photographic Meditations on Marginalization in a Pandemic Year

Catherine Wilkins, Ph.D.

Study the South, December 8, 2021

Social isolation is both a phrase and an experience that has defined the past year in the wake of the global COVID-19 pandemic. The images in photographer Jared Ragland’s ongoing body of work, What Has Been Will Be Again, expressly evoke the loneliness that has characterized this period; solitary subjects inhabit these frames, and many images in the series are devoid of people altogether. One can imagine the photographer, alone, navigating deserted landscapes with only a camera as his companion, documenting the recent ravaging of the public sphere. Yet, while the theme is certainly au courant, What Has Been... features subjects for whom social isolation is nothing new. This body of photographs, instead, makes a case for a long history of isolation and alienation in the artist’s home state – one that has exacted a costly human toll.

In this photographic survey that began in Fall 2020, Ragland has been working his way across Alabama following historical routes from America’s colonial era, documenting individuals and communities whose existence has been practically defined by economic and geographic isolation. The series features landscapes shot in tiny rural towns plagued by generational poverty and the exploitation of the environment, as evidenced by dispossessed storefronts, homes, and infrastructure. Ragland also makes visible the often-overlooked inhabitants of these neglected places by producing powerful portraits of lone individuals. While we can provide little assistance or solace Ragland seems to insist that the simple act of bearing witness to the loneliness is important. As the viewer travels alongside the photographer, moving through his weeks on the road and simultaneously through deep time, a creeping realization sets in – that these subjects and spaces have been deliberately left to their own devices, to deteriorate or decay. Their isolation seems less accidental or temporal, and more a product of decades of willful neglect by a mainstream America only now starting to visualize what – and who – has been pushed out of our collective frame of vision.

The great paradox of What Has Been... is that it visualizes the very real social isolation that has had tangible consequences on the individuals and communities photographed, while simultaneously revealing connections across space, place, people, and time. In images subtly subversive to the overall aesthetic of loneliness, tree branches organically entwine, messages are exchanged via layers of marks on the landscape, power lines run alongside roads that stretch out toward the horizon. More overtly, by tying together events in Alabama’s centuries-long past with present-day issues, Ragland insists that it is impossible to view our current period outside of history. The confluence of the COVID-19 pandemic, Black Lives Matter movement, and seditious domestic terrorism marks our times as significant, but Ragland’s body of work shows that the isolation, socioeconomic inequalities, racism, and marginalization we’ve witnessed is not unprecedented.

What Has Been... speaks specifically to the mood of our moment while also asserting the timelessness of its themes of isolation by illustrating the perpetuated use of segregation and sequestration in service of the white supremacist myths of American individualism and exceptionalism. As viewers prepare to emerge from quarantine and rejoin “post-pandemic” society, Ragland asks us to bear witness to the people and places who cannot so easily shrug off the mantle of social isolation.

.....................................

What Has Been Will Be Again: An Expedition Through Alabama’s Troubled Legacies

Alexis Okeowo

VQR, Spring 2021

Not too long ago, the sky down South was dimming, turning down from the lemony warmth of the day, deepening into gold and rose and then lavender and gray, poking through the thick moss of the weeping willow trees all around the neighborhood where I was staying. I was in my hometown of Montgomery, Alabama, mostly there for work but partly there, as always, for a chance to gather myself. Every evening felt the same—lazy light, heavy air, a languorousness that never fails to feel decadent to someone who is not a resident. For some of those people—the ones, like myself, who grew up in Alabama and then moved elsewhere—we are doomed to forever being of two minds about our home state. The ugly often appears to be its most dominant feature, the history and present of willful exclusion and oppression; but the tenderness, the land and people that make so many choose to call it home, is right there alongside it.

In a non-plague year, I go to Alabama more than anywhere else—at least five or six times a year—which I explain to people by saying that I started writing a book about the state almost three years ago, but the truth is I traveled nearly as often even before that. It went like this: I would get on a plane from New York to Atlanta, then wait around the Atlanta airport for a while before boarding a much smaller plane to Montgomery; and then, after landing, meet my dad at baggage claim to drive the half hour to my parents’ house. Along the way, we’re greeted by everyone from an airport custodian to a guy in camouflage who’s likely carrying. The same thing happens when I’m running around town and encountering people: We greet, talk, try to find out who we are, what matters to us—a regional custom of connecting to each other.

In these photos, photographer Jared Ragland returns home to Alabama in order to, as he said, “critically explore Southern identity, marginalized communities, and the history of place”—big ideas that feel smaller when you start meeting people on the road. The state becomes increasingly intimate and hard to define, starting with stories from the southern tip of Alabama, a place of both Indian reservations and vividly-remembered Civil War battles, to its northern reaches, where working-class white folks and Latino immigrants live side by side. Ragland takes another look at the state’s psychic and geographical landscape in a time of crisis: health-wise, politically, ecologically, and economically.

Part of his visual journey had him follow the Spanish explorer and colonialist Hernando de Soto’s trail through Alabama in 1540, as a way to document the ghosts and people that now reside on its most holy lands: sites of American Indian removal, battlegrounds of the civil rights movement, old coal mines where one of his ancestors worked, places of ongoing economic and environmental strife. The land is haunted, true, but the people living and working on it are determined to forge their own paths.

There are the things we all tend to know about Alabama. As Ragland told me, “From Native American genocide to slavery and secession, and from the fight for civil rights to the championing of Trumpist ideology, Alabama has stood at the nexus of American identity.” But there are also the things that only some of us know, and those truths about the tenderness of our home will take time to convince others of—through photos, writing, and however else we can make our experiences known. Because, as Ragland says, “it’s a complicated place, simultaneously beautiful and horrifying—full of instances where the abject and beautiful mysteriously intersect.” And importantly, it’s home, to Ragland, me, and a whole host of motley people—and that in itself makes it worthy of exploration, again and again.

.....................................

- Jared Ragland, Catherine Wilkins. “What Has Been Will Be Again,” Southern Cultures. January 21, 2024.

- Jared Ragland, Catherine Wilkins. “What Has Been Will Be Again: Photographic Meditations on Social Isolation in Alabama,” Study the South. Decemeber 8, 2021.

- Jared Ragland, Alexis Okeowo. “What Has Been Will Be Again,” VQR. Volume 97, Number 1, Spring 2021.

- Daniel George. “Jared Ragland: What Has Been Will Be Again,” Lenscratch. September 10, 2021.

Select Solo Exhibitions:

- Union Grove Gallery, University of Alabama at Huntsville, Huntsville, AL, January 2026 (forthcoming)

- SRO Gallery, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, January 2024

- Center for the Study of Southern Culture, University of Mississippi, Oxford, MS February 27-March 31, 2023

- Auburn University at Montgomery, Montgomery, AL, October 2022

- The Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, Montgomery, AL, June 18–Sept. 11, 2022

- The Do Good Fund, Columbus, GA, May 4–June 16, 2022

Select Group Exhibitions:

- Currents, Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans, LA, December 2024-January 2025

- As Pretty Does, Alabama Contemporary Art Center, Mobile, AL, August-October 2024

- Invisible Architectures|Social Contracts, Maryland Art Place, Baltimore, MD, Spring 2024

- Context 2024, Filter Photo, Chicago, IL, September-October 2024

- Unbound13!, Candela Books + Gallery, Richmond, VA, July 2024

- Between Life and Land: Identity, Kimball Art Center, Park City, UT April-July 2023

- Parallel Lives: Photography, Identity, and Belonging, CPW, Kingston, NY, November 2022-February 2023

Select Awards:

- 2025 Center for Photographic Art Mid-Career Grant

- 2025 Brooklyn Darkroom Artist-in-Residence

- 2025 Lenscratch Art and History Award, First Place

- 2023 Gomma Black and White Awards, Finalist

- 2022 Aftermath Project Grant, Finalist

- 2022 Urbanautica Institute Awards, Category: Anthropology & Territories, Winner

- 2021 Photolucida Critical Mass TOP 50

- 2021 Royal Photographic Society International Photography Exhibition 163, Shortlist

- 2020 Magnum Foundation US Dispatches Grant

.....................................

Select Works:

Each image is produced as an archival pigment print, 21x24.5 inches

Photographic Meditations on Marginalization in a Pandemic Year

Catherine Wilkins, Ph.D.

Study the South, December 8, 2021

Social isolation is both a phrase and an experience that has defined the past year in the wake of the global COVID-19 pandemic. The images in photographer Jared Ragland’s ongoing body of work, What Has Been Will Be Again, expressly evoke the loneliness that has characterized this period; solitary subjects inhabit these frames, and many images in the series are devoid of people altogether. One can imagine the photographer, alone, navigating deserted landscapes with only a camera as his companion, documenting the recent ravaging of the public sphere. Yet, while the theme is certainly au courant, What Has Been... features subjects for whom social isolation is nothing new. This body of photographs, instead, makes a case for a long history of isolation and alienation in the artist’s home state – one that has exacted a costly human toll.

In this photographic survey that began in Fall 2020, Ragland has been working his way across Alabama following historical routes from America’s colonial era, documenting individuals and communities whose existence has been practically defined by economic and geographic isolation. The series features landscapes shot in tiny rural towns plagued by generational poverty and the exploitation of the environment, as evidenced by dispossessed storefronts, homes, and infrastructure. Ragland also makes visible the often-overlooked inhabitants of these neglected places by producing powerful portraits of lone individuals. While we can provide little assistance or solace Ragland seems to insist that the simple act of bearing witness to the loneliness is important. As the viewer travels alongside the photographer, moving through his weeks on the road and simultaneously through deep time, a creeping realization sets in – that these subjects and spaces have been deliberately left to their own devices, to deteriorate or decay. Their isolation seems less accidental or temporal, and more a product of decades of willful neglect by a mainstream America only now starting to visualize what – and who – has been pushed out of our collective frame of vision.

The great paradox of What Has Been... is that it visualizes the very real social isolation that has had tangible consequences on the individuals and communities photographed, while simultaneously revealing connections across space, place, people, and time. In images subtly subversive to the overall aesthetic of loneliness, tree branches organically entwine, messages are exchanged via layers of marks on the landscape, power lines run alongside roads that stretch out toward the horizon. More overtly, by tying together events in Alabama’s centuries-long past with present-day issues, Ragland insists that it is impossible to view our current period outside of history. The confluence of the COVID-19 pandemic, Black Lives Matter movement, and seditious domestic terrorism marks our times as significant, but Ragland’s body of work shows that the isolation, socioeconomic inequalities, racism, and marginalization we’ve witnessed is not unprecedented.

What Has Been... speaks specifically to the mood of our moment while also asserting the timelessness of its themes of isolation by illustrating the perpetuated use of segregation and sequestration in service of the white supremacist myths of American individualism and exceptionalism. As viewers prepare to emerge from quarantine and rejoin “post-pandemic” society, Ragland asks us to bear witness to the people and places who cannot so easily shrug off the mantle of social isolation.

.....................................

What Has Been Will Be Again: An Expedition Through Alabama’s Troubled Legacies

Alexis Okeowo

VQR, Spring 2021

Not too long ago, the sky down South was dimming, turning down from the lemony warmth of the day, deepening into gold and rose and then lavender and gray, poking through the thick moss of the weeping willow trees all around the neighborhood where I was staying. I was in my hometown of Montgomery, Alabama, mostly there for work but partly there, as always, for a chance to gather myself. Every evening felt the same—lazy light, heavy air, a languorousness that never fails to feel decadent to someone who is not a resident. For some of those people—the ones, like myself, who grew up in Alabama and then moved elsewhere—we are doomed to forever being of two minds about our home state. The ugly often appears to be its most dominant feature, the history and present of willful exclusion and oppression; but the tenderness, the land and people that make so many choose to call it home, is right there alongside it.

In a non-plague year, I go to Alabama more than anywhere else—at least five or six times a year—which I explain to people by saying that I started writing a book about the state almost three years ago, but the truth is I traveled nearly as often even before that. It went like this: I would get on a plane from New York to Atlanta, then wait around the Atlanta airport for a while before boarding a much smaller plane to Montgomery; and then, after landing, meet my dad at baggage claim to drive the half hour to my parents’ house. Along the way, we’re greeted by everyone from an airport custodian to a guy in camouflage who’s likely carrying. The same thing happens when I’m running around town and encountering people: We greet, talk, try to find out who we are, what matters to us—a regional custom of connecting to each other.

In these photos, photographer Jared Ragland returns home to Alabama in order to, as he said, “critically explore Southern identity, marginalized communities, and the history of place”—big ideas that feel smaller when you start meeting people on the road. The state becomes increasingly intimate and hard to define, starting with stories from the southern tip of Alabama, a place of both Indian reservations and vividly-remembered Civil War battles, to its northern reaches, where working-class white folks and Latino immigrants live side by side. Ragland takes another look at the state’s psychic and geographical landscape in a time of crisis: health-wise, politically, ecologically, and economically.

Part of his visual journey had him follow the Spanish explorer and colonialist Hernando de Soto’s trail through Alabama in 1540, as a way to document the ghosts and people that now reside on its most holy lands: sites of American Indian removal, battlegrounds of the civil rights movement, old coal mines where one of his ancestors worked, places of ongoing economic and environmental strife. The land is haunted, true, but the people living and working on it are determined to forge their own paths.

There are the things we all tend to know about Alabama. As Ragland told me, “From Native American genocide to slavery and secession, and from the fight for civil rights to the championing of Trumpist ideology, Alabama has stood at the nexus of American identity.” But there are also the things that only some of us know, and those truths about the tenderness of our home will take time to convince others of—through photos, writing, and however else we can make our experiences known. Because, as Ragland says, “it’s a complicated place, simultaneously beautiful and horrifying—full of instances where the abject and beautiful mysteriously intersect.” And importantly, it’s home, to Ragland, me, and a whole host of motley people—and that in itself makes it worthy of exploration, again and again.

.....................................